Understanding the power of learning curves: Solar Power

How german subsidies made solar cheap and why the same does not work for housing.

Germany is a small country compared to the rest of the world, both in terms of size and population. Its carbon emissions are a tiny fraction of the world’s carbon emissions. If Germany stopped producing CO2 tomorrow it would not really help with climate change. However, Germany has managed to have a lasting positive impact on global emissions by convincing most of the German population to get solar panels. This is a very condensed story of how this happened with a lot of rhetorical questions because I am a bad writer and don't know how to build natural segues. There is also a short section on housing at the end.

Germany is not a great country for solar. While it does have some very nice summer days, especially in late August, it is on the whole not very sunny. It has roughly the same solar potential as Alaska, which ranks 49th in the US (also see this). The mean "direct radiation" in Germany in 2022 was 3.36 kWh/m^2, with the sunniest place getting 3.8 kWh/m^2. As per the previous report, Interior Alaska gets an average of 3.4 kWh/m^2. So how did Germany convince so many Germans to get solar power? Money.

Germany introduced a so called feed-in-tariff to encourage its population to invest in solar. While the details change often, the idea is to pay a "tariff" to someone who sells electricity to the grid on top of the market price. This ensures safe returns in an otherwise volatile market. The tariff ranges from 12.88 ¢/kWh for "small rooftop systems" to 8.92 ¢/kWh for "large utility solar parks", although these numbers are from a few years ago. There are also tariffs for other types of renewable energy.

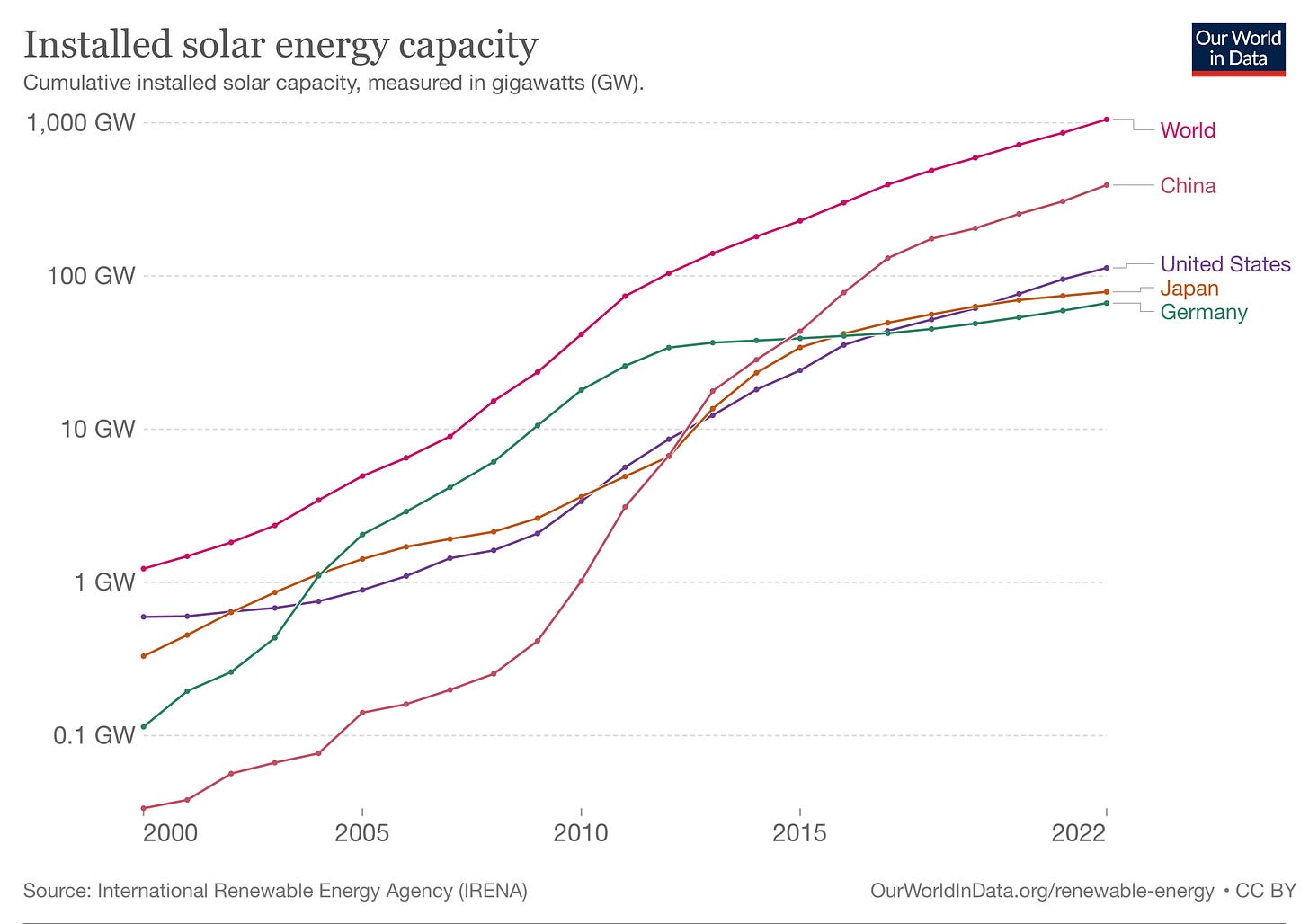

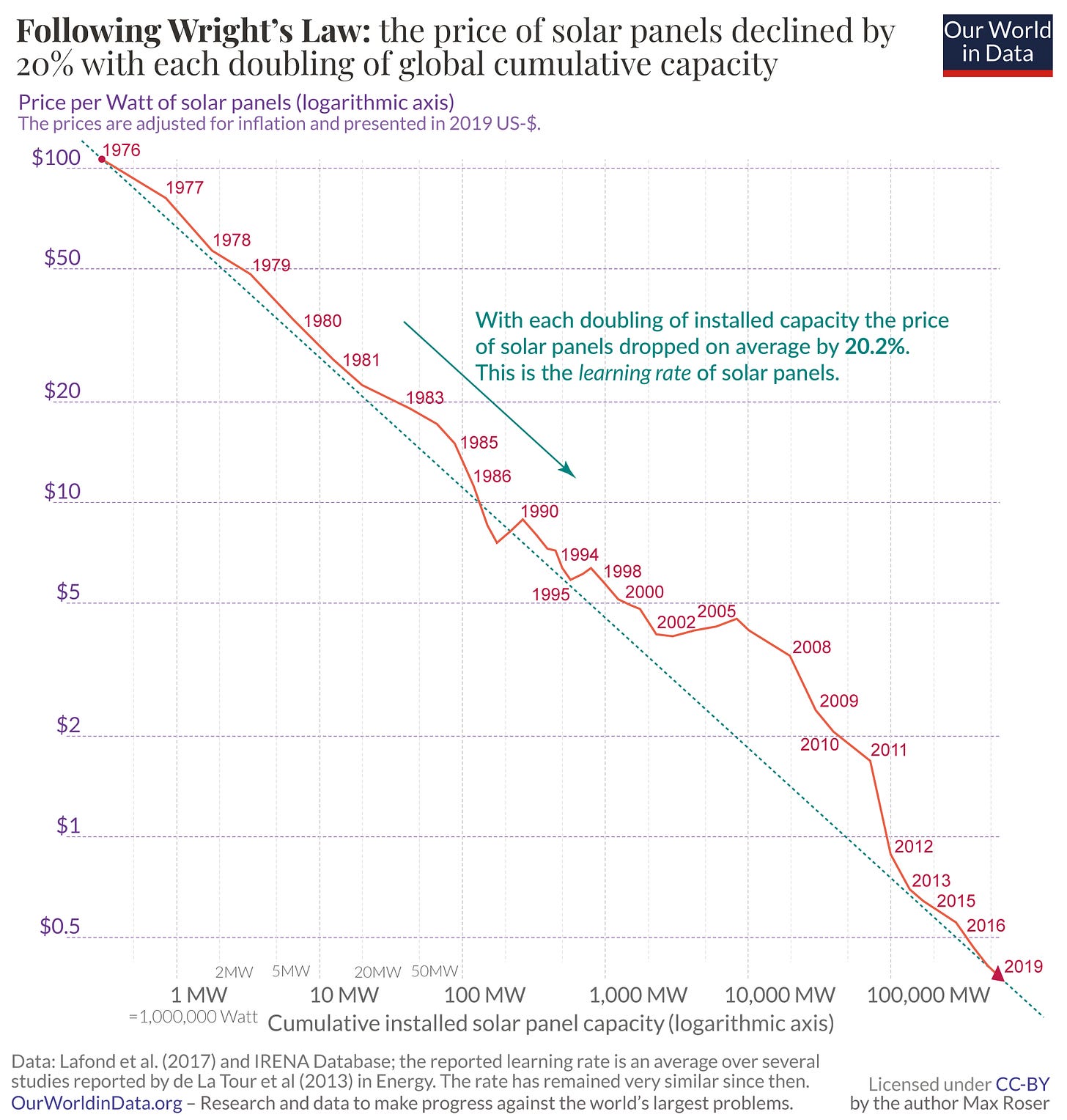

These strong incentives led Germany to be the country with the largest solar capacity (measured in GW) in the world from 2004 to 2015. Not per capita, but in total. Germany led by a wide margin: they had ~5x the capacity of Japan in 2010, the next closest contender. All this investment came at a crucial time for solar power. In the early 2000s global solar investment would have seriously slowed down if not for Germany as can be eyeballed from the chart below. This really matters because of learning curves. Just as Chips has Moore's Law, so Solar has Wright's Law. It states that the price of solar panels declines by ~20% for each doubling of global cumulative capacity. More generally this phenomenon is called a learning curve, meaning that manufacturers learn new ways to produce technologies more cheaply. Germany helped keep solar on this very important curve. Why does this happen?1

To understand why these solar subsidies worked it helped me to understand the flip-side and see why housing subsidies did not (and do not) work. The following list of facts are roughly true about Solar PVs, but also CPUs and GPUs and TVs: most of the cost is in R&D, the cost of the raw materials is fairly low, scaling supply is feasible, there is high demand, there are few exclusive rights / regulations (like in pharma or housing). The high demand ensures companies will keep investing in R&D. The limited regulation plus low material cost means that once production is up and running additional units are cheap. In particular, prices will naturally go down in this environment as competition will force prices to become close to the cost of raw materials and labor and shipping. The cutting edge can always still be expensive in these environments as it takes time for competition to catch up / copy, but once they do it means cheaper prices for all. Notably the bottleneck for cheaper / better products is R&D, which naturally attracts more investment as long as demand continues. The subsidies in Germany provided exactly this demand to keep the cycle going.

Warning: Throwing subsidies around to make things cheaper does not work most of the time. It only works in very particular situations where the money has the ability to flow to R&D. Now you might ask why not fund R&D directly? That is one for actual economists to answer and I bet it comes out in the wash. Either way, there needs to be a conceivable way for the product to actually become cheaper through more investment. For this to be true all of the conditions in the list I mentioned must hold. One example where they do not hold is in housing. The main thing that fails is regulation and red tape.

Houses do not lack in R&D. We know how to build a house. Raw material and labor is not getting a lot cheaper. In most places local governments just do not allow us to build more housing. It is a process that is artificially stopped by bureaucracy causing supply to severely lag behind the demand. That is the main reason why houses/apartments in cities are so much more expensive than somewhere rural or suburban.

The key thing that made solar cheap was giving people a chance to build a lot of solar! To make housing cheaper we need to give people the same opportunity to build a lot of housing.

Related: I just finished reading Chip Wars, I should probably write a post about it...